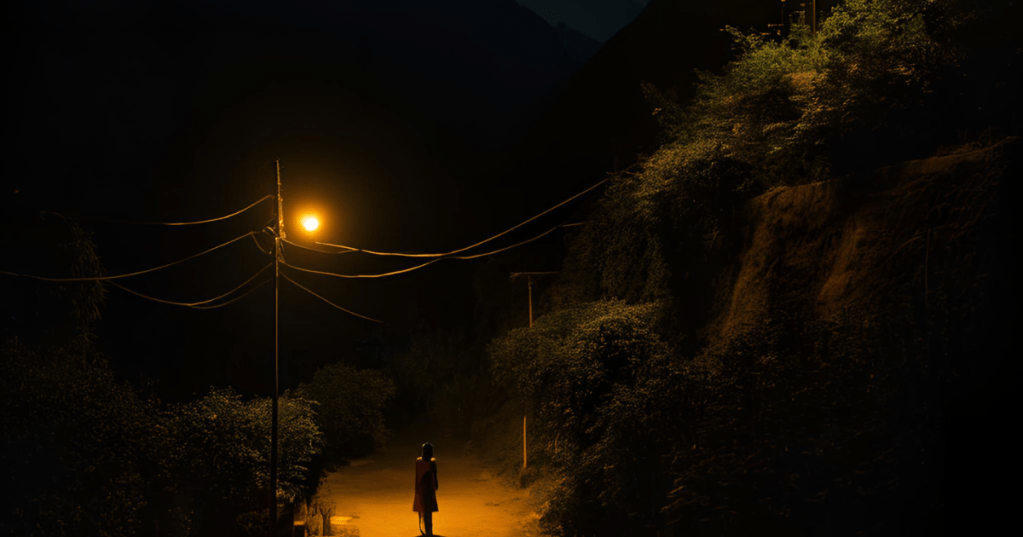

Perhaps it was the movies that first made me believe that memories had a gentle yellow sepia tone to them, that looking back, adds a warm softness to the edges of life—a softness I miss profusely.

But the cozy yellow of memories is not all an imagined invention; there is something of the real in it. I realized it standing on the street in front of what was once my childhood home.

Growing up one lives through an irony. The world around you is relatively smaller and bigger at the same time, as compared to when we are adults. You see, just as one grows out of their childhood clothes to the displeasure of middle-class mothers, you also grow out of childhood spaces. The washing of times shrinks them to you. Those spaces are fit for a miniature you. At the same time, as you grow, the world opens up for you, there is more of it that you have seen and traveled. Yet the fenced ground of my childhood remains in my memory the biggest of spaces.

These expansive spaces of my childhood are washed in a golden light.

I remember I would play outside till the daylight began to dim. In those days when the warm yellow street lights would switch on, they would do so with a crackling sound. Something about that light made the neighborhood more suited to the fantastical imagination. The flies would crowd around the light adding movement to it. They looked like alive specks of light. Later in my life when I read about the particle nature of the light, that is how I imagined it, and still do. Under those lights and those hours, magic could exist.

As the evening darkened, more sounds and smells would follow—the sound of whistles of pressure cookers going off, followed by the warm delicious smell of food. But we (the neighborhood kids) wouldn’t budge until our mothers started to holler us home for dinner. The moment our mothers called us was when we registered the force of hunger, and what hunger it was, and what delicious food. As privileged as it sounds, I must say, I miss feeling hungry like that. That pure feeling of hunger and the satisfaction of warm food— I was lucky to have it. That is the kind of hungry children should feel, after running around for hours; it was not the deficient hunger of starvation, but the primal feeling in all its rawness, one that forced you to be present, one that made you appreciate food.

Those were the last of the times when I was completely living in the present moment; I lost that hunger—for food and for life, that is, in part, when my childhood ended.

Now, for practical reasons that I am unaware of, the yellow street lights have been replaced by stark white ones. They stab my eyes even from a distance. Gone is the softness under which I spent my ever-so-brief childhood. Under these white lights the spaces I inhabit have contracted. As a child, I imagined that adults had more freedom, but the older I have gotten, the more the world has entrapped me.

My house is in a small village not far from my childhood home; a ten-minute ride by car. It is surrounded by trees and farms, but for all its beauty and spread-out landscape, it’s restrictive to me.

Like most villages my village is a close-knit community. Which means it keeps a check on its people, and deviations are never encouraged. Your way of living cannot be misaligned with the community’s way of living.

It is remarkable how swiftly gossip—accompanied by moral judgment—spreads in my village. Once that happens to you (and it will), rest assured your world is about to shrink a little more. Eventually, there comes a time when, either you have to amputate parts of yourself and your life to fit there, or you have to leave. You’d be surprised how often people make the former bargain. The terrifying part is that humans can get used to anything, even the lack of freedom.

Villages are especially not the kindest of spaces for women; you are made aware that you are under constant watch. These bright white street lights of my village do seem to be in collusion with the watchful eyes of villagers. Seldom do I stand underneath it, but whenever I have, I have felt exposed. Exposed like one is to the calculative hostility of an interrogation room—that is the character the white light imparts the street. In the dark, under the white light, the floating white eyes of people thread through you. These very threads weave your personal cage. Then over the years you learn to be less free and then less uncomfortable with the lack of freedom. You make it your new normal in order to survive.

The magic that once indulged me in life is lost under these clinical lights. I am forced to acknowledge a limiting reality. Some of you might be of the opinion that it is essential to face the real rather than find repose in the magical. To a degree, I agree with you. But, you have to believe in magic to create it. Curbing imagination curbs the real; maybe this is another way our world shrinks as we grow up.

The last time I ran freely, it was under the warm yellow street lights, I don’t get to run anymore—not in a woman’s body, under white lights aiding critical eyes.

Somewhere I had read you cannot go back home once you leave it. Now, standing at the site of what was once my childhood home, I understood what it meant. My home rests with the golden glow of my memories; This right here is an abandoned ruin waiting to be raided to the ground, and that is the least of the reasons why I cannot return to it.

Then it happened: the crackle of the street light switching on, followed by the kind embrace of the yellow light. They hadn’t changed this light yet. It is because this area is home to no one now, so no one cared to replace it. How odd, that it is indifference that preserved the magic of this place.

A friend told me that we need to learn to view the world around us with a childlike fascination to savor life. Life is so sad because learning this childlike fascination is not easy. This is perhaps an Indian household thing, but I remember how excited we were about the snacks served to relatives. Our mothers would get so embarrassed and tell us that we were looking at food like we didn’t get any at home. It was just this simple; things would excite me, life would excite me. As a kid you could find me enchanted by balloons, and now I don’t see the point of them.

Now even my imaginings have become rooted, so seeing the regular with fascination is tricky. To free myself, first I need to free my imagination.

Forgive me, I lied, I left before the street light could switch on, that way I could imagine it to be the same old yellow street light. I must remember/imagine running to be able to run again, and so it is crucial that the light of my childhood glows a warm golden.